by Chidera Anthony-Wise*

Farmers might just be the new pharmacists.

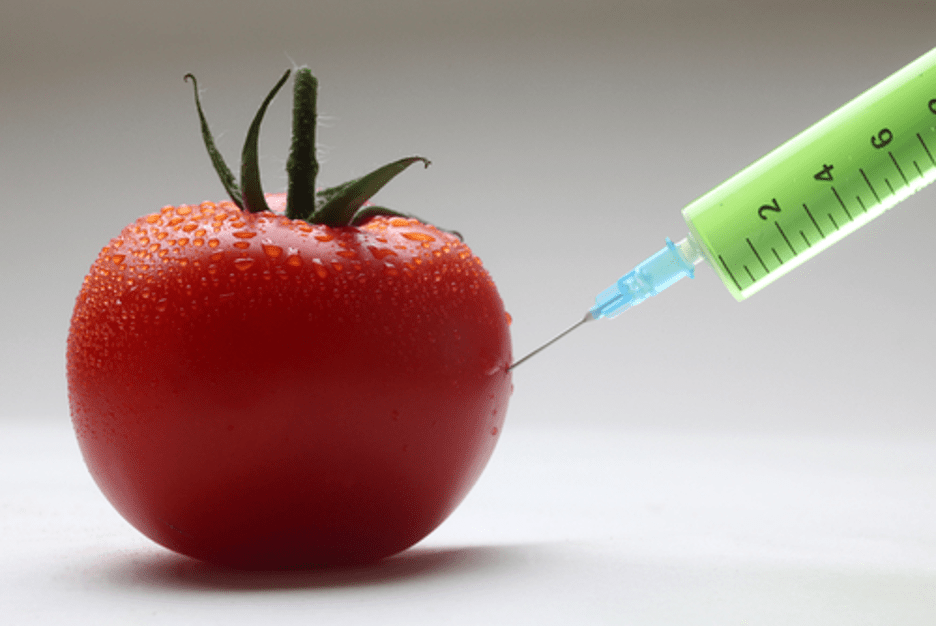

Through scientific breakthroughs, plant products can be genetically modified to deliver immunity against diseases. These “edible vaccines” present remarkable possibilities at the intersection of agriculture and biotechnology.

One such possibility is to assist immunization efforts on national and global scales. Many low-income nations and US cities such as Chelsea, Massachusetts and Hyde Park, New York lack essential access to vaccines due to expensive costs, maintenance challenges, and improper distribution. The use of common fruits and vegetables as vehicles to immunity could, for this reason, be a tool toward achieving equity. In addition to disease protection, edible vaccines can also be used to alleviate malnutrition because highly nutritious foods, such as tomatoes, lettuce, bananas, corn, and rice, are frequently used as host plants.

History

In the 1990s, Dr. Charles Arntzen and his team spearheaded the production of an early edible vaccine, a surface protein antigen A derived from Streptococcus mutans successfully expressed in tobacco. This edible vaccine has the capability of alleviating infectious endocarditis, or bacteria occupation in the inner lining of the heart. Arntzen and his colleagues went on to develop a heat-labile toxin, B subunit in potatoes to potentially treat hepatitis B. There is a large focus on protein production in relation to edible vaccine efficacy, as antibodies and protective white blood cells are created by the immune system in the presence of spike (S) proteins. Therefore, to showcase that plant-derived hepatitis B surface antigen could generate a mucosal immune response, host plant potatoes have been optimized to become protein-rich. Other edible vaccine examples include transgenic carrots against HIV and E coli, lettuce against malaria, and spinach against rabies.

The initial research and development of edible vaccines was prompted by the limitations of conventional vaccines. Some safety concerns of conventional vaccines include inactivation failures and subsequent reversions of virulent forms along with the lack of proper quality control tests, leading to vaccine contamination with unknown viruses and bacteria. For many countries, composing a sustainable financial plan to continue affording vaccines and maintaining conducive storage temperatures are additional limitations. Edible vaccines, on the other hand, have great advantages that should be considered by governing bodies. Such vaccines are created with antigenic proteins that do not possess pathogenic genes, which is protective of immunocompromised patients. Moreover, the production of plant-based vaccines is quite efficient. With just 200 acres of land, enough host plants can be cultivated to administer edible hepatitis B vaccines to 1.363 billion people. An additional advantage for feeble healthcare systems is that there is no need for highly-skilled medical personnel with edible vaccines. With general training and doctor’s approval via prescription, civilians can take agency of their health and wellness by biting into a tomato.

The primary production mechanism of edible vaccines is agrobacterium-based transformation. Through this process, a gene which codes for an antigenic protein is isolated and subsequently integrated into a “gene vehicle” or a vector. The vector is introduced to the genome of the host plant which expresses the antigen of interest to elicit an immune response.

Case study: Tomatoes as COVID-19 Vaccines

By means of bioinformatics and computational genetic engineering, Mexican scientists are determining suitable antigens for edible COVID-19 vaccines via tomatoes. The research is pioneered by Daniel Garza, a researcher and entrepreneur, hailing from the Institute of Biotechnology of the Autonomous University of Nuevo León in Mexico. Garza has been in the business of disease prevention for some time, working to discover an antigen candidate for an Ebola vaccine since 2018. However, with the dire nature of the pandemic, Garza and his team shifted their primary focus to developing a tomato COVID-19 vaccine, using the same foundational research from the Ebola vaccine.

Garza’s research is not the first attempt to create a plant-based COVID-19 vaccine. The biotechnology company known as Medicago aims to create a COVID-19 vaccine expressed through tobacco, hoping to produce 10 million doses per month upon US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval. Kentucky Bioporcessing, based in the US, has conducted preclinical trials for a tobacco COVID-19 vaccine as well, predicting to produce three million per week. The tobacco vaccines would likely be an oral formulation such as a capsule or tablet. The public sector, namely the University of California, San Diego, strives to manufacture microneedle path-vaccines using proteins derived from genetically modified plants.

Legal Realities and Implications

Despite the promising future of edible vaccines, regulations may limit extensive experimentation. The president of Mexico, an opponent of genetically modified crops, placed a scientist with similar views as director of the organization in charge of the national science budget. This poses a threat to the advancement of Garza’s research. He expressed his thoughts on the matter by stating “Given the current contingency situation for the COVID-19, we are experiencing, it will undoubtedly make us rethink the legislation of the GMOs that apply not only in Mexico but in Latin America…The benefits of biotechnology must be shown to society not as an evil, but as an effective solution to many of the problems that we currently have in the region.”

Similarly, legislative bills placing cautionary parameters upon edible vaccines were introduced in the US. Bill TN HB32/SB88 in Tennessee “[p]rohibits the manufacture, sale, or delivery, holding, or offering for sale of any food that contains a vaccine or vaccine material unless the food labeling contains a conspicuous notification of the presence of the vaccine or vaccine material in the food.” Because the research of edible vaccines is complex, such mandates are sensible. This form of regulation is needed to establish informed consent among the general public. Furthermore, the FDA has not formally approved any edible vaccine for consumption or commercial use. The novelty of the technology may raise concerns among the general population, which already includes individuals who are against genetically modified food altogether. This reality highlights the importance of meticulous research and well-established clinical trials. As laws and research develop, governments also must consider how much land will be dedicated to the full production of edible vaccines, while not severely decreasing the acreage used for the dietary agriculture industry. Overall, it is imperative for lawmakers to analyze the future of edible vaccines and establish regulatory frameworks to ensure maximum safety and health.

*Chidera Anthony-Wise is a Spring 2024 graduate of UCLA, earning a degree in Human Biology and Society. She is passionate about healthcare equity for low-income, communities of color through fortified legislation and policy.