by Trey Catanzaro*

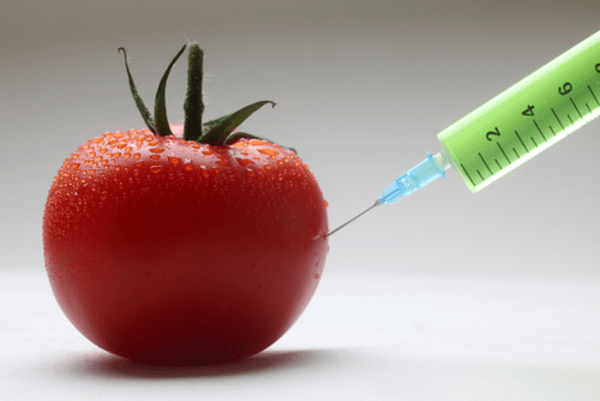

If you ask most Americans what food additives they may “generally recognize as safe,” it is highly unlikely that they would answer “propyl paraben” or “beta hydroxy acid.” Rather, they may say vinegar, olive oil, or black pepper. In fact, when asked about what “generally recognized as safe” means, a national poll found that 77 percent of respondents thought that standard meant the FDA has evaluated the product and determined it to be safe. However, under current FDA regulations, a company may self-determine whether its product is “generally recognized as safe” under FDA guidelines, and then bring it to market without even notifying the FDA as to its existence. In other words, there are currently thousands of chemicals in everyday food that the FDA has no clue even exist. As succinctly stated by the former Deputy Commissioner for Food at the FDA, “[w]e simply do not have the information to vouch for the safety of many of these chemicals.”

Most chemical additives enter the American food supply due to an exception in FDA pre-market review for ingredients that are generally recognized as safe (GRAS). In legislation drafted in 1958 to address the rising issue of additives in food, Congress specifically exempted certain ingredients which were “generally recognized . . . to be safe under the conditions of [their] intended use” from the definition of additives. Therefore, anything determined to be GRAS would not be subject to pre-market review and approval by the FDA. At the time of passing the amendment, the reasoning for the GRAS exemption was so that ingredients that had long been used in foods without apparent harmful effects, such as salt, sugar and other familiar substances, would not have to undergo extensive testing to be used in food products. However, the GRAS exemption continued to expand, eventually permitting companies to self-determine whether their ingredient was GRAS, and giving them the choice of whether or not to notify the FDA of their GRAS determination.

Under the present iteration of the rule, companies’ GRAS determinations are filled with a litany of conflicts of interest. Rather than relying on peer-reviewed data, companies often convene panels of experts to make a GRAS determination. These panels are frequently made up of the same small group of individuals who have made a career out of GRAS panel participation. To put this in perspective, a comprehensive study looked at convened GRAS determination panels from the year 2015 to 2020, and, out of the 732 panel positions available, there were a mere 7 individuals who filled 339 (46%) of these positions. Their determinations of safety are often never sent to the FDA for review. Further, even if a GRAS determination is sent to the FDA for notification, which is not required, and valid concerns are raised about the safety of the product, this does not always preclude the product from coming to market. Companies have the ability to voluntarily withdraw their petitions should they foresee unfavorable results from the FDA’s review. Therefore, after receiving health concerns from the FDA based on its review of a GRAS notification, the company may then withdraw its notification and continue to market the product. The FDA will then issue a letter of withdrawal without acknowledging the safety concerns raised during the review.

Continue reading “In Search of Greener GRAS: How Regulatory Policy has Created the American Diet and How to Fix it” →

You must be logged in to post a comment.