by Heliya Izadpanah and Lavanya Sathyamurthy*

This is Part I of a two-part post.

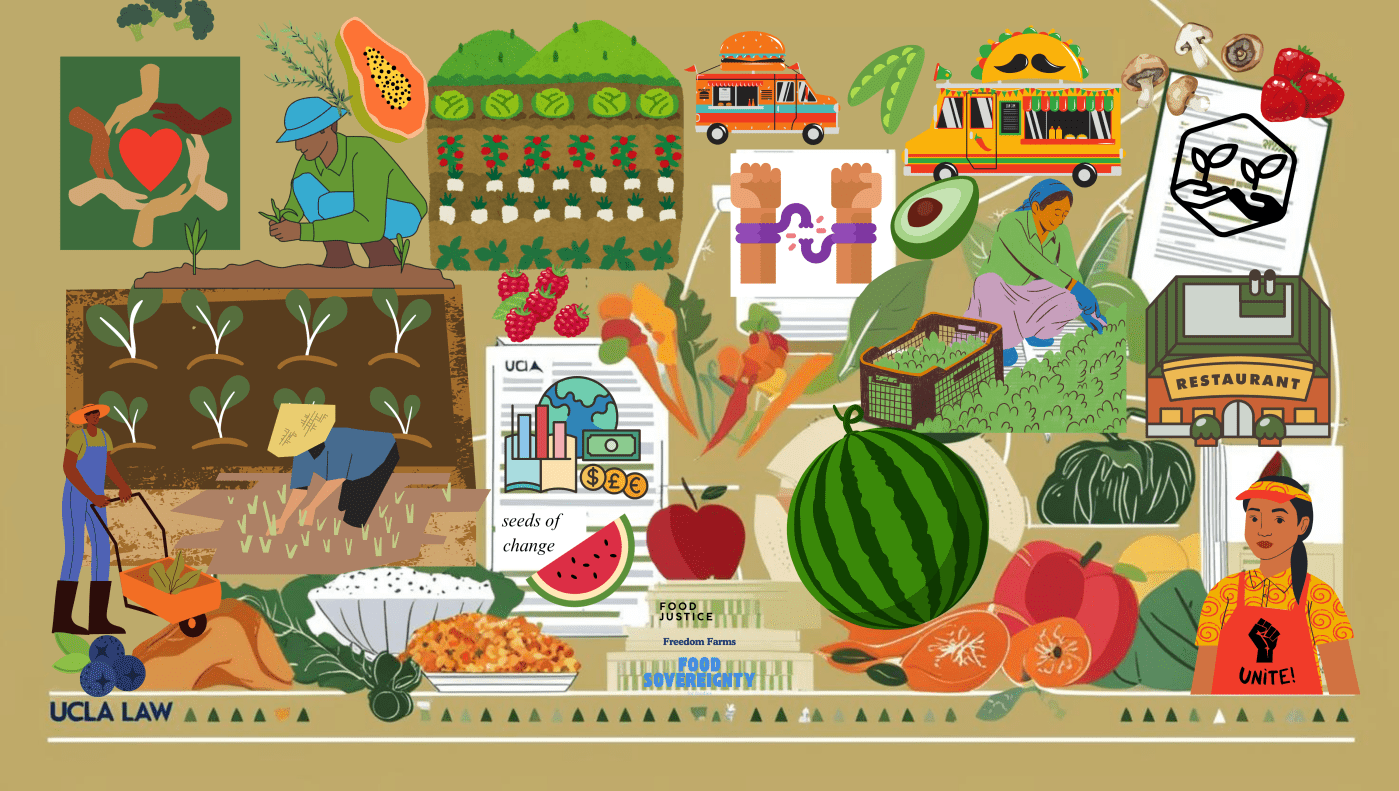

Dreaming of Food Justice in Law

By Heliya Izadpanah

UCLA Law was my dream school. Like many law schools, it catered to my interests in human rights law and environmental law. But what made the decision to attend UCLA Law a no-brainer were two rare institutional assets–its groundbreaking Critical Race Studies program paired with one of the few Food Law programs then existing in the nation.

I was a passionate advocate for food systems justice. We all interact with food daily, yet its production and distribution are rarely observed in modern society. People often don’t know the conditions under which their food is produced or the legal machines maintaining these systems. But when it comes down to it, it’s virtually impossible to identify even a single food item that isn’t riddled with disparities of race, rights, and inequity. From growing food, to harvesting, processing, transportation, access, and health outcomes, every aspect of food systems is steeped in disparities of race, gender, wealth, status, and ability.

As a teenager, I was inspired by Black Power activists and other POC leaders steeped in food systems—Fannie Lou Hamer and the Freedom Farms Collective, Black Panthers like Erika Huggins who created the nation’s first free breakfast program, and Shirley Chisholm, a key architect of WIC and SNAP programs. Similarly, I looked up to the founding organizers of Farmworkers United—Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez—for their achievements in food production. Each of these leaders knew the power of food, revealing its power to either hold one in oppression or to act as a focal point for movement building, community power, sovereignty, and emancipation. I was eager to learn how to use law as a tool for food systems justice and get involved in the food law program.

The Resnick Center has tried to incorporate discussions of diversity, equity, and inclusion into its offerings. It has featured an agroecology class, a food and social justice issues podcast series, lessons on food access, and a diverse global health collaborative. Students and faculty have worked with the Williams Center to advocate for LGBQTA+ inclusion in the SNAP program and promote agricultural insurance to reduce farmers’ economic precarity. But with only two full-time faculty, the Center’s capacity was limited.

When I arrived at law school, I was disappointed to find no class offered that was dedicated to fighting abuse and racial injustice in food systems. Often at food law events, I found myself to be one of the only people of color in the room at one of the nation’s most diverse law schools. This ran contrary to my prior food systems experiences, working on urban farms, studying various cultural perceptions on alternative proteins, developing food ethics programming and podcasts, and organizing basic needs initiatives.

I didn’t blame my BIPOC peers. Like most white-collar fields, law and policy are generally White spaces where inequity is reinforced by systemic barriers and elitist requirements. The Food Law Space is no exception. Why partake when we do not see ourselves and issues critical to our well-being represented in a field? I, myself, strayed from food law, instead immersing myself in Human Rights, Public Interest law, and Critical Race Studies.

At the Promise Institute for Human Rights, I found Professor Cathy Sweetser, who often litigates cases on slavery, human trafficking, and child labor in food systems. I found Professor Victor Narro in the labor law department, who often works with low-wage and immigrant workers crucial to food production. Their work presented abundant opportunity for discussion on racial equity and food systems. It made clear to me food’s proximity to the production or reduction of social, cultural, economic, and civil rights. But none of these relationships or these professors’ work was being explored in our food law program. Likewise, my Critical Race Studies did not touch on food activism or scholarship either.

How were we not talking more about the racial capitalism that constitutes food systems and the legal structures that maintain it? After all, we live and feed in a nation built on racial dominance. Our global food systems continue to prosper on racial capitalism. The United States’ origins begin with the genocide of Indigenous Peoples, paired with the destruction of native, sustainable, and diverse foodscapes. These were replaced with centuries of agricultural monoculture, enslavement of African and Afro-Descendant Peoples, and sharecropping.

Today, domestic agriculture thrives off the intentional criminalization of movement and migration, extracting backbreaking labor at low wages on the backs of primarily Latiné and BIPOC populations. Globalized markets, racism, and neoliberalism foster similar racial subordination. Of the roughly 30-50 million people currently subject to modern slavery—human trafficking, forced labor (both state-imposed and private), debt bondage, descent-based slavery, and child labor—the vast majority are BIPOC, and food production spaces are no exception.

Why were there no global food rights initiatives, not just here, but at any law school? I wanted to see the Resnick Center doing more to address injustice, to foster global racial solidarity, and to use its positionality to advance core rights in the production and consumption of food. In an age of racial retrenchment, neocolonialism, and racial erasure, could we not do more?

At the Resnick Center’s 10th Anniversary Conference, Lavanya had similar questions. Particularly galvanized by hearing Washington and Lee Law Professor Tammi Etheridge speak about her interest in food law and critical race theory, Lavanya asked, “How do we incorporate Critical Race Studies into food law education? Where do we start?”

“Here and now.” The answer to my qualms and Lavanya’s questions came in the form of encouragement from Professor Michael Roberts, who took our questions and criticisms to heart. With the endorsement of Resnick Center and Critical Race Studies faculty, we began a project to transform food law education nationally. We seek to bring discussions of race, migration, class, and intersectionality out of the shadows of food law through a holistic, systems-based approach.

We ground this movement in two key schools of thought:

First, recognizing our faculty’s extraordinary achievements in developing and contributing to Critical Race Studies programs and scholarship amid retrenchist backlash to reform, we seek to embalm discussions of racial inequity and power into food law curricula.

Second, recognizing our common struggles in a globalized society and the inherent limitations of a purely Westphalian approach, we seek to incorporate and promote Third World Approaches to International Law as much as possible.

We hope this project will become a movement, not just at UCLA and the Law School, but for food systems and racial justice thinkers around the country. We invite practitioners, academics, teachers, and students at UCLA and across the country to join us in this pursuit and grow it for years to come.

Equipped with a strong national food justice network, an abundance of bright students passionate about equity, and a growing number of renowned legal scholars focused on the intersections of race, food, and inequity such as Andrea Freeman, Christopher R. Leslie, and Ernesto Hernández-López, our potential is unlimited.

We hope you will join us in bringing race, gender, class, and migration to the forefront of food law. This is but a beginning.

Continued in Part II.

*Heliya Izadpanah and Lavanya Sathyamurthy are students at UCLA Law School.

You must be logged in to post a comment.